On August 27, 1946, in a minor bullring in Linares, a Podunk lead-mining town in southern Spain, Manuel Laureano Rodriguez, known as Manolete, was mortally wounded, gored in the right leg by a nasty bull that insisted on radically departing from the script.

Manolete was the son, grandson, nephew, and great-nephew of toreros, but as a child he was a bookworm mama's boy with little interest in going outside, much less in staring down bulls with a cape and a sword. But from 1939 on, he became a legend. He had affairs with beautiful actresses, palled around with both Picasso and Franco (separately; Picasso and Franco were not pals), and captivated a nation with old-school "passing." He brought back classics like the "manoletina," where he turned his back to the bull and used his muleta to bring the animal into his body, spinning away as the horns rushed within centimeters of his waist. Even dolled up in pink silk with bespoke socks from Barcelona, Manolete embodied the ideal of the true Spaniard: sangfroid punctuated with a magician's flair when confronted with angry beasts 10 times his size. But it was all over when Islero caught him in the Andalusian heat of that August afternoon. The crowd yelped and then fell into a guilty silence. Manolete was dragged away to the ring infirmary. The finest horn doctor in Spain came down from Madrid to lead an all-night vigil. At 5 a.m. a priest delivered last rites. Manolete died later in the day on the 28th. He was 30 years old. On the orders of Generalissimo Franco himself, state radio played only funeral dirges for days afterward. It was the end of an era. The last great bullfighter was dead. A nation mourned.

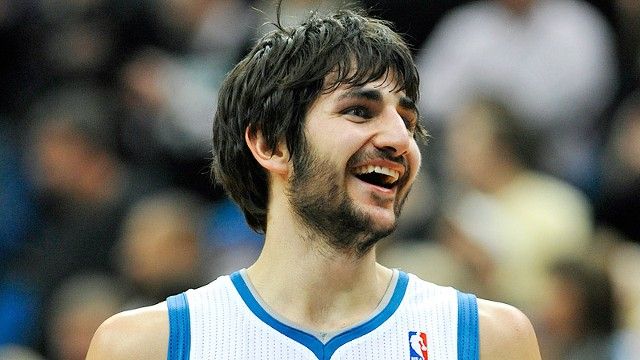

And that's exactly how every basketball fan in Minnesota felt when Ricky Rubio tore the ACL in his left knee on March 9, 2012:1 Wolves Nation mourned. With Kevin Love playing out of his mind in Ricky's absence, the team clung to the frame of the playoff picture for two weeks after The Injury, before completely falling off by the end of the month. But losing Ricky goes deeper than the lost chance to sneak into the postseason as an 8-seed.

Minnesotans may not have that exact same Spanish duende — we don't have the same aficionados, like a Lorca or a Hemingway, to put this into context — but we can feel sorry for ourselves with the best of them. We're the home of the Minnesota Vikings. Native son Bob Dylan recorded Blood on the Tracks, the greatest breakup album of all time, in a south Minneapolis studio. And we gave the world F. Scott Fitzgerald, who wrote fatalist shit like, "The sentimental person thinks things will last — the romantic person has a desperate confidence that they won't." So in a way, we're strangely equipped for this kind of mini-tragedy.

Beyond the Wolves, it's been a terrible stretch for Minnesota sports.2 We've been waiting for a savior, and we waited for this particular savior for more than two years, since we drafted Rubio fifth overall in 2009.3 I mean, it was shocking that the sexy pick in the draft fell to us in the first place: At this point, T-Wolves lottery disappointment is kind of a thing around here, like snow in April, or unresolved stadium debates. Finally, some good fortune, or at least a GM arrogant enough to say fuck it, we'll take him. And then we found out he wasn't coming after all, and then there were the inevitable rumors that his mother believed it was too cold up here, and that he wanted to play in a bigger market. It instantly brought up our collective Midwestern abandonment issues. Of course the beautiful boy from Barcelona didn't want to come here. Nobody that pretty or talented or unusual ever wants to be here, the home of unbearable Scandinavian conformity and nasty winter.4

And then on June 2, in the middle of an unexpectedly early swoon by the Twins, the Wolves actually signed Ricky Rubio, seemingly out of nowhere. It's not exactly that we had forgotten about him, but Kurt Rambis's terrible coaching made it really hard to keep the faith alive. But ladies and gentlemen … we got him! So despite the initial Twitter shrug from Kevin Love, and the reports from abroad that Ricky was no longer any good, and the delay caused by the lockout, by the time the Wolves' preseason rolled around, the coming of Rubio verged on the messianic.5

We didn't know exactly what we were expecting from a player who most of us had only seen on YouTube, but when he got here, Ricky definitely approximated it. Even new coach Rick Adelman admitted that he didn't know what he was getting until he saw Ricky in training camp — and then he figured it out quickly. On opening night, Luke Ridnour started, but Ricky played the entire fourth quarter against the Thunder in a surprisingly back-and-forth game. He did the same thing against LeBron James and the Heat a couple nights later. "He earned that from me," Adelman said about riding Ricky during crunch time. "He's the type of guy you want to have the ball in the fourth quarter."

Rubio's Ricky Jay-like passing became a regular on SportsCenter and NBA.com. The team looked like it was having fun — sharing the ball, congratulating each other after big plays. Sports Illustrated wrote a big feature on Rubio. The Minnesota Timberwolves were getting national pub and nobody in the locker room was grumbling about the Spanish rookie getting all the attention — instead, the team seemed to be basking in it.6 Then, in an inadvertent nod to Minnesota's hockey heritage, when the Wolves beat the world champs in their second week, Ricky found Anthony Tolliver for the dagger 3 on a bounce pass right through Dirk Nowitzki's five hole. He handled the ball most of the time (his 38 percent assist percentage ranked eighth in the league among point guards at the time of his injury), and in the first month of the season his shot looked better than advertised, but it was his defense that was the biggest difference maker.7 His ability to anticipate on offense translates to the other end of the court — he was among the leaders in steals before he went out. And his length (6-foot-4 with a 6-foot-9 wingspan) and technique allow him to stay off his man an extra step and contest straight up on both jump shots and drives. He made tough fourth-quarter stops against opposing guards like Tony Parker and Chauncey Billups — guys who've torched the Wolves in the past. The anti-JaVale McGee, he just looks like he knows what he's doing out there. But don't take my word for it: On the Sports Guy's podcast Larry Bird himself copped to "watching him every night."

But Rubio's draw goes beyond the alley-oops and the defense, even the winning. This wasn't just about basketball — we already had Kevin Love, whom Charles Barkley has called "the best power forward in the game," after all. But Rubio, with his indie-band mop top and his Spanish nose and his Maybelline-ready eyelashes, had something else.8 Women loved him. Hipsters loved him. Rich Republican courtside types loved him. When the newspapers quoted him (they didn't even bother to correct his English) you could hear his soft immigrant accent and feel his formal Spanish politeness. Once, when I asked if there was a specific coach who helped teach him defensive fundamentals, he demurred, "We had a lot of coaches there. It was like four or five from my young teams. And they all teach me good things, especially on defense." His clichés (example: "You try to run to try to have freedom and try to have fun and sometimes you have to take care of the ball") seemed right from a Lonely Planet: NBA phrase book. In the fourth quarter, when the scoreboard ran the video of him yelling "Let's goooooooooooooo!," there's a collective two-second delay to suppress our giggling before we roar approval. He became our adopted son, our surrogate little brother. When he tossed the ball three rows into the stands (rarely), or missed four jumpers in a row (not as rarely as you'd like — Ricky was a 34 percent shooter in February), the Target Center fans didn't groan or admonish him, they felt protective, the way you'd feel watching your Little Leaguer whiff. For those first 41 games, we tolerated mistakes, like flopping on a layup, or making a horrible turnover, as growing pains.

Rubio's flashy passing never seemed to be in service to himself, only an attempt to help the team using the element of surprise. (David Kahn, Rubio's no. 1 fan, characterizes it as "efficient flair, not superficial flair.") He seemed like an antidote to the self-centered AAU-ness of not only present-day professional basketball, but to present-day kids, present-day life. As Wolves assistant coach Bill Bayno told me after practice one time, because of video games and iPads and cable TV, "I don't think as many kids in this era truly love to play the game as they did 20 years ago. But Ricky's different."

So when Rubio went down, it felt operatically tragic. This wasn't a dying bullfighter, or even a dead bull, but this was our golden boy who lived to play. In that way, the whole thing felt inevitable, a tragedy more ancient than just a torn-up knee. The ritualized beats of that Friday night were evocative of Hemingway's death in the afternoon. First, the outraged roar of the crowd dissipating into quiet shock. Then, the instantly rendered irrelevance of the game's outcome along with the play-by-play man's postgame analysis (just another Wolves loss to the Lakers, after all). Later, the "rare trip" by the father figure, in this case Coach Adelman, to the training room after the game (according to a tweet from Wolves beat writer Jerry Zgoda, "he emerged quickly, looking glum"). Finally, the stiff upper lip on the part of the beatified victim (Ricky sent out a hopeful tweet about his obviously doomed MRI to come, followed by a link to the Kony 2012 Internet video). And the terrible certainty of the worst radiating from everybody else, from inner sanctum out to the general public (my fellow press-row buddies leaked grim assessments from Wolves staffers, and every other Rubio fan on Twitter, from Dwyane Wade to Marc Stein to my brother Kevin, just generally freaked the fuck out).

Where were you when Rubio went down? To my great personal shame, I wasn't even in the building that night. I was traveling north on a freeway that runs parallel to Highway 61 — missing my first home game of the year, in a van with my girlfriend, headed north to Hayward, Wisconsin, for my birthday, listening to Wolves-Lakers on the radio. Here I was, feeling doubly, maybe even triply, guilty, feeling sorry for myself and sorry for Ricky and sorry for myself for feeling more sorry for myself than sorry for Ricky: basically struggling not to ruin my (and, crucially, my girlfriend's) weekend over an injured basketball player. Why did I feel this way? Was it because I'd been working on this story for a long time and I missed the night the kid went down? Was that why? That didn't seem noble. Was this a lesson in karma? Did this happen because I abandoned him? Was it somehow my fault that the matador was gored in the bullring? I wondered how Kevin Love felt. Because of back spasms, the Timberwolves MVP was sitting out the Lakers game, home in his condo downtown. Was he wondering if things would've been different if he had played? Strangely, Alejandro "Aito" Reneses was also at the game that night. This was Ricky's first head coach, the first guy to totally believe in the kid: Aito gave Ricky his first professional minutes at the age of 14, and as Olympic coach, he started Ricky in the gold medal game in Beijing when he was only 17. Aito was in the Target Center because the Spanish Coaches Association was holding its convention this week in Minneapolis. Did Aito feel responsible? Was his presence some weird cosmic weight, too much weight for that fragile ligament? The New Yorker had a writer on press row for the game, in town all week to do a big story on Rubio — did he feel guilty? SLAM Magazine had just hit newsstands, and Ricky and Kevin were on the cover (the cover image mirrors a pose that KG and Stephon Marbury struck on a SLAM cover in '99),9 the writer of that piece was at home watching the NBA League Pass darlings. And he actually copped to the SLAM cover curse on Twitter. So there's denial and bargaining, all jumbled together and twisted in your stomach. And then in our first game without Ricky, we lost to Sacramento at home: yup, depression.

On Wednesday, March 21, Ricky went under Dr. Richard Steadman's knife in Vail. He's been updating his Facebook with the most adorable candid photography of post-op major reconstructive knee surgery in human history. Maybe it's time for acceptance: He's not a dead matador, but he's not coming back this season either. The team has gravely missed him on both ends of the floor. We still have nearly enough guys to suit up and play out the season, and we can still score — see Love's 51 against the Thunder on March 23 — but we can't stop anybody and the ball distribution was shaky enough in a blowout loss to Sacramento that J.J. Barea and Kevin had to be separated before coming to blows. (The anger stage, obviously.)

But here's the thing: There's been so much emotional tumult surrounding St. Ricky, all this love and anxiety and heartbreak, and it's all been compressed into this four-game-a-week, no-time-for-practice season, with the schedule serving as the official reason the team has refused to provide much access to him or his family or his friends. We still don't know much about this guy. We don't really understand exactly what we've lost. And that might be romantic enough for The Great Gatsby, but now that we're finally past the initial euphoria of the 2009 NBA draft, and the weird two-season interregnum, and this final burst of crushing disappointment, now that Ricky is gone for awhile, maybe we can begin to penetrate all this exotic Spanish mystique and figure out why he can consistently put the ball within a centimeter of the rim on an alley-oop, while consistently going 1-for-7 from the field. Or why he seems so friendly and cute while being so closed off and wary of the media. How exactly did Ricky Rubio become Ricky Rubio?

t's not a surprise; Rubio has been a pro since he was 14 years old." Without fail, that's what every opposing player answers when you ask him about how the young Spaniard is doing so well in the NBA. LeBron said it, Dirk said it, Kobe said it.10 If you hear this answer enough times, you get the impression that the now 21-year-old Rubio was once a Bieber-like prodigy who was out there wrapping the basketball around his back at a full sprint and dishing it to a trailing wing between his legs as a toddler.

And it turns out that yes, Ricky really was a basketball prodigy, but it turns out that being a basketball prodigy in Spain, especially in Catalonia, is dramatically different than being a prodigy in America. You can tell from the arenas: When I went to Barcelona's Palau Blaugrana to see Ricky in a playoff game against Real Madrid in 2010, it felt like a big college game at a place like Cameron Indoor. It was packed with around 8,000 fans, and the crowd was fuming with anti-Madrid hatred,11 complete with the separatist Catalonian flag and antagonistic songs and chants, but the scoreboard, with those big red digital numbers, looked like it was handed down from my old high school gym in White Bear Lake, Minnesota. The second thing I noticed is that Ricky stunk: He scored five points, with two assists and three turnovers, without playing at all in crunch time. But these players were much bigger and hairier than college kids — Ricky looked like a 19-year-old playing with grown men. The only way I was able to console myself was to think about all the 19-year-olds that have stunk in the NBA.

In fact, by the time Ricky was draft eligible, all those teenage busts seemed to be finally registering with NBA front offices: Finally, there was some stigma attached to the childlike part of childlike geniuses. And Ricky not only looked like a child, he appeared to be hanging on to his childhood. The Sports Illustrated story from the first month of this season made it a point to mention both his obsession with The Lion King and the teddy bear collection he kept in his apartment in El Masnou. Before the '09 draft, there was a rumor going around that the Sacramento Kings passed on Ricky because his mother, Tona, cut his steak for him during a meeting with the GM.12 His parents didn't even allow the media to talk to him until he was 18, and other than that SI story, this season Wolves brass has limited access to Ricky to 10-minute interviews after practice. You get the sense that they are trying to keep their prodigy happy. When encountering the initial resistance, I asked David Kahn why the team is so protective of Ricky. And he responded in typically pugnacious style: He blamed it on Bill Simmons. "Neither of us are listening to any of the bullshit right now," Kahn says. "It's kind of ironic, the founder of your site has probably been the most hysterical, overdramatic poster child for why people should pay no mind to people who don't know."

What we do know is that Ricky grew up in El Masnou, a pretty bedroom community on the Mediterranean about 25 minutes from downtown Barcelona. With three ACB teams in Barcelona proper, and 27 clubs at various levels throughout Catalonia, this is far and away the most fertile basketball region in Spain;13 it's produced the Gasol brothers and Rudy Fernandez in addition to Rubio. Rubio himself hails from a basketball family, sort of a laid-back Catalan version of the Hurleys; his father, Esteve Rubio, coached girls and boys at Montmelo, another small club about 15 minutes inland from El Masnou.14 But when Esteve started working nights as a mechanic at Alcon, the giant eye-care chemical lab in El Masnou, he took a long break from coaching. Marc Rubio, Ricky's older brother by two and a half years, was also a basketball whiz kid — he went pro when he was 16.15 But back when Marc was an 8-year-old, he started playing for the El Masnou minis. Even though he was only 5, Marc's little brother didn't want to be left out.

Josep Maria Margall, a swingman on the 1984 Spanish national team that won silver in Los Angeles, was the technical director of El Masnou when Ricky played there. He remembers Rubio's first practice: "Tona [Ricky's mother] brought him to the gym with Marc," he says. "Little Ricky was 5. I was surprised, but I told her, 'All right, as long as he doesn't cry, I'll take care of him on the court.'" Ricky didn't cry. "He actually played the same level or better than the children Marc was playing." His older brother was a bigger player — "a little chubby," according to Margall — and a much better shooter (still is), but Ricky quickly learned how to play a more complete game in order to compete with the older, stronger kids. By the time Ricky was 8, he was dribbling through his legs and passing behind his back. And his defense stood out back then too: On some Saturday afternoon games he would have 22 or 23 steals against the other infantils.

There was one hiccup in the young Rubio's rapid development at El Masnou. "He was so good with both hands," Margall says. "But I told Esteve that you're going to have to decide which hand he shoots with." According to Margall, Ricky decided on his right hand, but his dominant eye is left. "This might have been the beginning of his problems."

Ricky Rubio's jump shot is his fatal flaw, and it has to be a much clearer window into his basketball psychology than why he loves The Lion King or a teddy bear collection or the time that his mommy cut his steak in Sacramento. For two years before his arrival in Minnesota, the Spanish press deconstructed the physics of Ricky's J the way conservative legal scholars have deconstructed Obamacare. They broke down the positioning of Ricky's left hand, the angle of his release, where he held the ball in relation to his head. The tabloids fabricated stories about the friction between Ricky's personal shooting coach and the Barcelona head coach, Xavi Pascual. And if Ricky's NBA season hadn't ended so abruptly, the same thing would have happened here — in the six games coming out of the All-Star break, Ricky was shooting just over 25 percent, and that's including going 5-for-12 the night he got hurt against the Lakers.

Margall believes that Ricky has never worked out the kink that this natural lefty problem creates because of two reasons: (1) Ricky's overall game was so great so quickly that he skipped an important developmental level. At the age of 14 — when most Spanish kids are playing "juniors" — he was called up to the pro team at Joventut Badalona in the ACB League, the top level of Spanish ball. "In the pros, winning and losing is tantamount," Margall says. "And Ricky wasn't a good enough shooter to take 15 shots a game and miss a majority of them." And (2), Badalona was a young team, but most of the players were still at least six years older than Ricky, and many of them much older than that, and he wanted to fit in, and the best way to fit in was to get these guys shots.

But what really exacerbated the flaw in his game were his two years in Barcelona. After Regal Barcelona bought out his weird Badalona contract for $5 million (the Wolves were limited by NBA rules to a $500,000 contribution), he found himself on a veteran, championship-contending club, and the pressure on winning now was even greater (in fact, they won the Euroleague Finals in Ricky's first season). Barcelona coach Pascual, in contrast to the no-drama Aito, was a 37-year-old half-court control freak who likes calling a play every possession. After bringing the ball upcourt and making the first pass to initiate the offense, Ricky was often found spotting up in the corner for a chance to brick another 3. He was up and down that first season in Barcelona, and then mostly down the second. Barcelona turned on its favorite son.

Jarinn Akana is Ricky Rubio's personal shooting coach. He's an L.A.-based trainer and scout who worked in the Bucks organization before superagent Dan Fegan hired him to work with European ballplayers signed with the massive Lagardère sports agency. Akana has been working with Rubio the last several offseasons, both in L.A. and at Ricky's basketball camp in the mountains around Girona in northern Catalonia. He also serves as sort of a general counsel and go-between — he accompanied Ricky and his father on their first trip to Minneapolis to meet with Kahn and owner Glen Taylor after the draft in '09. He's the only one in Ricky's inner circle who's made himself available for extensive interviews this season.

"You have to understand, man," Akana says in his Hawaiian drawl, "in Spain, Ricky was hyped up to be the Second Coming. You know how it is in the media, when you're good you're good and they're all over you, and when you're bad you're bad they're all over you too." According to Akana, when the Spanish media started going crypto-fascist tea party on Ricky's shot, he started to resent them. And then when he blew up this year, and every ink-stained wretch in every locker room in America wanted their five minutes, well, it must have brought up bad memories, in a second language.

But Akana does corroborate my assessment of Ricky's J. "Ricky tends to get two hands on the ball shooting it," he says. "So we work on a lot of one-hand shooting and keeping the ball on the right side of the face or your head instead of in the middle." To correct that, Akana has Ricky work on simply getting close to the hoop and shooting with one hand, focusing on putting a lot of arc on the ball — a drill that happened to result in a bizarre Guinness World Record on All-Star Saturday, when Ricky made 18 shots in 60 seconds from behind the backboard.

"Yeah! I was right there," Akana says. "I've been in shooting workouts with Ricky where he doesn't miss." He says the biggest issue isn't mechanics, but rather Ricky's psychology. "The number-one important thing in the U.S. for any kid — I don't care who you are or where you come from — is to shoot the ball and score. When you play pickup, that's all you do." But in Catalonia, it's more about organized ball, and less about pickup. "Ricky is not an individual player. His first thought is, 'I wanna win, and how do I do that? If I score 30 points, and we don't win, it really doesn't matter. If I can get that guy 20 points and that guy 10 and the other guy 15, we're going to win games that way.' And now he understands the game a little more and sometimes he shoots 15 times, 16 times. Because they're forcing them to do it and he realizes that he has to do it. Even if he's missing all those shots, it's still helping to get guys open. You know, in a crazy way."

All of Ricky's coaches talk about this: how much Ricky thinks about the game. Bayno says that Ricky's obsession with basketball isn't confined to the court: He has an insatiable appetite for film. Adelman points out that Ricky knows not only what he should be doing on any given offensive read, but what his four teammates should be doing and in turn, what the players defending them should be doing. "You see a cutter go through the lane," Adelman says, "and some guys just see that cutter — they don't see what's around that cutter." Ricky sees that that cutter created space for somebody else, or even tipped off a cascade of problems that will eventually create even more space, as the defense rushes to rectify the system. It's how grand masters exploit a mistake in chess: Once your offensive system is a step ahead of the defensive system, it's important to keep the bad guys guessing on where you're going next. "You can't make the obvious play," Adelman says. "And guys like Ricky, they understand that."

So maybe Ricky's wonky jump shot is just an unfortunate symptom of how much he thinks about everything. A great bounce pass is often about vision and touch combined with a feel for what's going to happen next — it's where instinct and basketball IQ intersect most naturally. But a jump shot is more like a golfer's putting stroke — the most unnatural basketball act, its perfection is more dependent on individual, mechanical repetition than any other coordinated movement in the game. And when it's learned, it's learned. A study from (Grantland's own) Jonah Lehrer's book on neuroscience, How We Decide, shows that when experienced golfers are forced to think about their putts, they hit significantly worse shots. So maybe Ricky's decision to stymie any significant investigation into the weakest part of his game is a prudent one.

But this is America, not Spain, and in America we are even more focused on who takes the shot and who doesn't. We're always arguing with each other about who has the courage to shoot the big one, even if the percentages aren't in that shooter's favor. In some ways, a shot that Ricky took against the Clippers in a game in L.A. on January 20 looms larger than any of his passes or steals this season. It was Ricky's cherry-tree moment, his ESPN instant parable. He had been 0-for-10 from the field, but in the waning moments, Luke Ridnour drove the lane and kicked to Derrick Williams, who hit Ricky with the extra pass on the wing — and he swished a 3 to tie the game. The Wolves ended up winning on a Kevin Love buzzer-beater. 0-for-10 and frustrated, but he forgot about the frustration and took the big shot. "It just shows you that he's not afraid to take the shot," Coach Adelman says. "He's not afraid to keep playing; that's just who he is."

But does it tell you if he'll overcome his knee injury? Or does it tell you that he'll stay in Minnesota for a contract that doesn't make Kevin Love any angrier at David Kahn than he already is?16 Or does it tell you if Ricky has it in him to be the type of point guard where playoff victories will eventually mean more to him than being buddies with his teammates? Is Ricky Rubio anything like his hero Magic Johnson, the type of point guard who will make the Timberwolves championship contenders?

And what if he had missed that shot?

Maybe someday Rubio will sit down and allow some reporter to dig deep. Until then we're forced to draw our psychological conclusions from case history like that shot against the Clippers. But Coach Aito believes there may be a better, perhaps more instructive folk hero moment that we can deconstruct. Sure, it's another one from the old country, but maybe it will translate in time. Aito tells an anecdote about a famous Ricky moment in the Under-16 European championship in 2006. Ricky's line against Russia was especially gaudy that night — in a 110-106 double-overtime win, Ricky scored 51 points, with 24 rebounds and seven steals — but it was a play at the end of the second overtime that encapsulated how his brain works. Back then, under FIBA rules, the 24-second clock didn't start until possession. "With 27 seconds left," Aito says, "they inbounded the ball to Ricky." But instead of grabbing the ball with his hands, Aito says, "Ricky took the ball with his chest," like a soccer player, nudging it upcourt; the ball indisputably in his control, but maybe not quite in his possession. Ricky Rubio: half 14-year-old point guard, half slimy defense attorney. "After three seconds," Aito says, "he grabbed the ball. In this way, he was thinking that they have the last possession if they don't make foul."

Aito says two weeks later, when Ricky reported to Badalona, Aito's starting point guard Elmer Bennett asked him about the play. "Bennett asked, "Por que piensas tanto?" Aito says. "Or, 'Why do you think so much?'"

"This is an important concept for Ricky."

The last time I spoke to Ricky Rubio was in the locker room after the Portland game, on the Wednesday before fate gored his knee. All of his teammates had showered, dressed, and dipped out, and after quietly fielding questions from the scrum of usual suspects, the Timberwolves PR guy opened the floor for questions in Spanish. After Canal Plus asked a couple questions, my translator brought up that play in the Russia game. He repeated Bennett's inquiry: "Por que piensas tanto?" Ricky's response wasn't just another basketball cliché (especially in Spanish).

"Me gusta pensar y ser inteligente," he said. "Intento siempre aprovechar lo maximo las ventajas del juego y llevar las reglas al limite. Yo creo que, bueno, que era una opcion, que al final del cuarto era para que tuviera toda la posición entera, y bueno lo puse en practica."17

Steve Marsh would like to thank Mikal Arnold for his help translating all the Spanish speakers.

No comments:

Post a Comment